Virtuent Insights #1

Navigating Uncertainty in the Banking Sector

Virtuent is an investment firm focused on the U.S. banking sector. Our focus on the sector is due to it being an inefficient part of the equity market. As data scientists, we like that it’s a sector with more stocks than the average sub-sector, and a more granular level of data than most sectors thanks to regulatory filings.

In this post, we wanted to share what we’re seeing in the data as it relates to the U.S. banking sector. Today, while there are signs for optimism, clarity is needed on a few key risks, and we provide our takeaways after discussing these items. The post concludes with the most popular questions we are getting right now on the sector.

Let’s start with the good news.

The Bulls.

There are a few indicators that should give market participants comfort that the situation is not universally as dire as it may have seemed initially.

Insider activity, which shows that bank executives and directors are actively buying their own stock, is currently flashing a strong bullish signal. This data is especially important right now because executives and directors have the best data of what is going on within their bank. It is noteworthy the extent to which executives and directors have been buying stock, at the fastest pace since the second quarter of 2020. While some purchases may be signaling, many of these are material buys.

The other signal relates to deposit activity. The market’s key concern has been that smaller banks are experiencing bank runs, not unlike what was experienced at SVB, Signature Bank and First Republic. Here, old-fashioned channel checks by many covering banks, and many under-followed headlines on community banks and now on regional banks, point to no unusual deposit activity for most banks during this period and that deposit outflows at regional banks have slowed considerably in recent days.

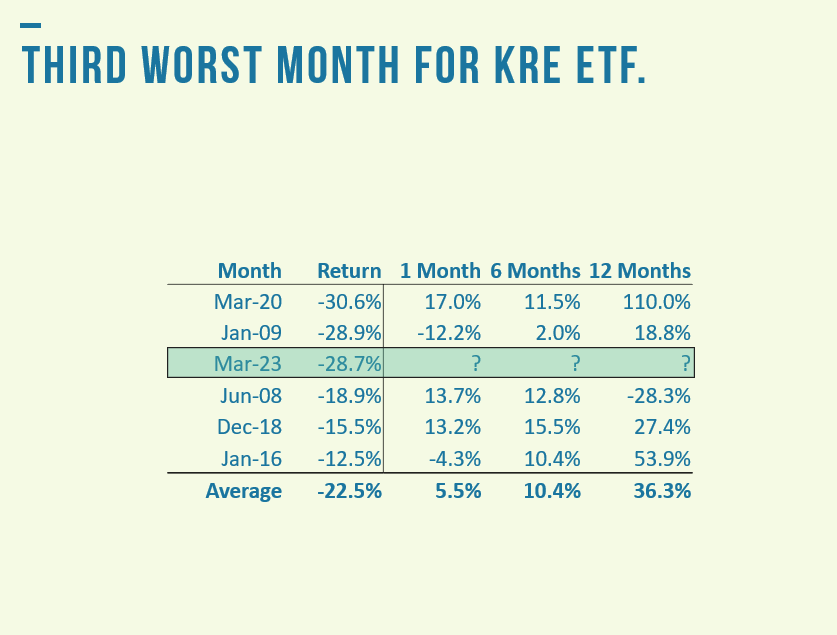

Another signal is a result of the price action this month. The SPDR S&P Regional Banking ETF is a liquid proxy for regional banks. The ETF launched in June 2006, which offers us just over 200 months of data. Through last Friday, the month-to-date return for the ETF left it at its third worst month in history. Here, it is worth noting that the forward 1-, 6- and 12-month return for the ETF has historically been above average when bank stocks have reached this level of a drawdown.

While this data indicates that the situation may not be as universally concerning as many may think, it’s also important to cover the uncertainty that’s weighing on the sector, and factors that have the potential to weigh on bank stocks in the coming months. This is covered in the next section.

The Bears.

In the short-term, there are two outstanding risks that, if resolved, would help to increase clarity for bank stocks and the overall industry.

The first risk is that First Republic in its current state is creating an overhang for sector. First Republic is exploring a sale or a capital raise. It’s unclear what First Republic would fetch in a sale, but we worry that a sale could wipe out the equity and, at First Republic’s current size, any capital raise would materially dilute existing shareholders. Neither is a great option. However, once one of these paths is chosen, it should help to remove a degree of uncertainty.

The second risk relates to deposit insurance. SVB was at risk of a bank run because SVB had one of the industry’s highest shares of uninsured deposits. It was unclear until the Sunday after SVB failed that uninsured depositors would be insured, and it is still not clear how future cases will be handled by regulators. Secretary Yellen, in her Senate testimony last week, sparked a sharp sell-off in bank stocks, when she stated that blanket deposit insurance was not actively being considered at the moment.

In the medium-term, there are three factors that will matter, impacting bank stocks in different ways. Here, security selection matters.

The first factor is regulation. It is highly likely that Washington will enact legislation that prevents this specific situation from happening again. Elizabeth Warren is already discussing tougher constraints and more stringent regulation for banks with greater than $50 billion in assets. While regulation is likely, it seems most likely to affect the larger regional banks with assets between $50 and $250 billion in assets, a range that included SVB, First Republic and Signature Bank as of year-end 2022.

The second is it would be shocking if we aren’t talking about loan-level delinquencies, charge-offs and credit losses later this year. Our expectation is that the stress banks’ asset-liability managers have been under gets shifted to banks’ credit officers in the second half of 2023. This is the slower-moving risk in banks that has been dormant for many years now, and it seems to be awakening due to the knock-on effects of higher interest rates and draining of liquidity from the financial system.

Below are delinquency trends for Ally Financial’s portfolio of retail auto loans.

The third is that the banking industry being in the headlines will pressure net interest margins in the coming months, as deposit rates adjust higher due to savers now being aware of the rates available to them. This has the potential to lead to weaker guidance from executives on earnings calls and the sell-side revising estimates lower as a result. While this could very well weigh on the sector as a whole, this will affect some banks more than others, particularly those without a competitive funding advantage.

The Takeaways.

In the coming months, we could see lower lows as banks issue weaker guidance, the sell-side revises estimates lower, regionals face more stringent regulation and banks see a growth in delinquent loans. Yet, this isn’t the first time banks have faced a rising cost of funds and an inverted yield curve. Regional banks now offer 5% to 7% dividend yields, and insiders are actively buying stock. We’re now 40%+ off last year’s highs and in the midst of one of the worst months in the last 20 years for regional banks. And, these outlier months have historically been followed by above average returns. This is noteworthy when the vast majority of banks have seen no unusual deposit activity, and this has been the catalyst for a large part of this de-rating.

The Questions.

1) Will the rapid rise in the fed funds rate not cause depositors to rapidly withdraw funds from banks?

This question is driven not just by the collapse of SVB, Signature Bank and First Republic, but also by deposit growth at U.S. banks rolling over late last year after reaching historic highs thanks to COVID-induced stimulus measures.

Many struggle to understand why someone would keep funds in a bank account not earning 4.5%, if a saver could earn 4.5% in a 3-month T-Bill. The reasons vary from depositor to depositor and from bank to bank, but one commonality across the industry is that larger depositors typically receive other benefits from their bank, often in the form of an ancillary service or a loan from bankers who understand nuances related to the niche in which their business operates.

Here, it is also worth looking at the historical precedent. The chart below shows the cost of funds for FDIC-insured banks back to 1984 and compares it to the fed funds rate. There has always been a lag between a bank’s cost of funds and the fed funds rate. When the Fed hikes interest rates, the cost of funds for the banking industry increases, but it hasn’t historically gotten as high as the fed funds rate, or ever exceeded it until the Fed starts to cut interest rates.

For context, PacWest Bancorp, a company that has been near the center of this storm with a stock that is down 65.6% just this month, saw its spot deposit rate increase from 1.71% at December 31, 2022 to 2.04% at March 20, 2023. While some of the cost of funds’ increases this quarter will be material and will affect net interest margins in the near-term, it is not as dramatic as most seem to think, that the cost of funds is going to see an immediate adjustment to the fed funds rate overnight.

To be clear, the cost of funds for the banking industry will increase from current levels. It is unlikely to stay below 2% for much longer, but it is also unlikely to exceed 4%, unless the Fed were to need to hike more aggressively.

2) How did we get here, and why are so many banks sitting on unrealized losses in their securities portfolios?

When deposits at banks surged in 2020 and early 2021 as a result of COVID-induced stimulus measures, there was a spike in the size of banks’ securities portfolios. It takes time for banks to originate loans, and such a rapid growth in deposits led to questions of how sticky would be these deposits, and bankers needed to maintain sufficient levels of liquidity against these new liabilities. As such, many purchased liquid securities such as Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities, in an effort to earn a yield greater than zero while preserving liquidity.

Shortly thereafter, the Fed, in an effort to control inflation, embarked on one of its fastest hiking cycles in history, raising the fed funds rate from 0.0% to 4.5% in a twelve-month period. One of the consequences of this hiking was banks faced unrealized losses on securities they had just purchased. For many banks, these mark-to-market losses were material. The challenge is if a bank is forced to sell these assets. These unrealized losses are realized, creating a hole in a bank’s balance sheet that must be filled. This can happen during a bank run. As depositors withdraw funds, part of the bank’s funding goes away, forcing them to sell assets.

In this scenario, existing shareholders of banks face the prospect of material dilution, which, unsurprisingly, leads to a decline in bank stocks. This decline in stock prices makes it even harder for the bank to raise new capital.

3) But, how are banks going to be able to make money with short-term interest rates above long-term interest rates?

The concern around the banking industry’s rising cost of funds stems from the shape of the yield curve, or the spread between short-term and long-term interest rates. It’s common to hear that banks borrow short and lend long. What this means is that the most common liability of a bank, its deposits, are shorter-term in nature. A depositor may have daily liquidity through a savings account, or seek to earn a higher yield through a CD. Either way, these liabilities are short-term relative to a bank’s assets, which are generally longer-term loans made by a bank.

This leads many to assume that banks will not be able to stay profitable if the yield curve is inverted, or if short-term interest rates are above long-term interest rates. History and data can guide us on the validity of this concern as well. The green line in the below chart shows the yield curve spread, the difference between the 2 year and the 10 year U.S. Treasury yield, back to 1984. The blue line shows the banking industry’s net interest margins (“NIMs”), or the spread between the rate that banks earn on loans they make and the rate that they pay to depositors.

For most of the last forty years, bank NIMs have actually stayed in a pretty tight range of 3% to 4%, despite the banking industry facing an inverted yield curve on multiple occasions. Here again, there is historical precedent.

If you have any questions, please hit reply to this post or email us at info@virtuent.com. If you are an accredited investor and interested in learning more about Virtuent, please contact us at info@virtuent.com.